"The Lungs of the Planet"

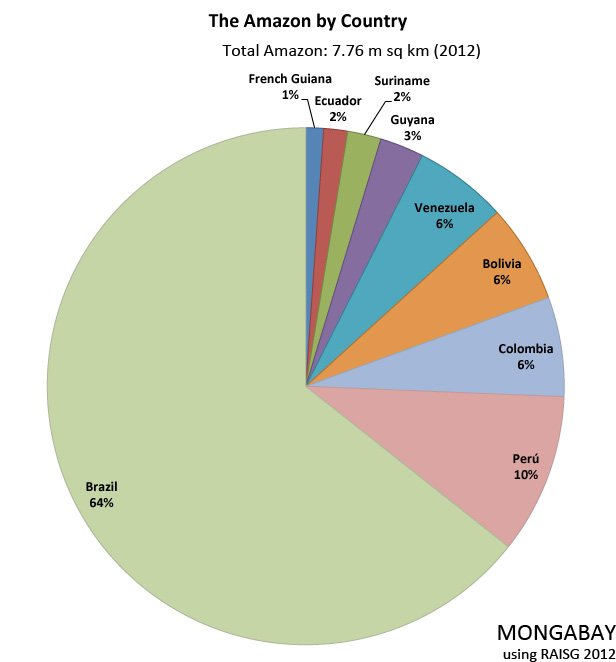

The Amazon rainforest is the largest rainforest in the world, located in the drainage basin of the Amazon River and its tributaries. It covers about 40% of South America and includes parts of eight rapidly developing South American countries. Nearly two-thirds of it is located within the country of Brazil (1). The rainforest is roughly the size of the forty-eight contiguous United States.

|

| http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/where_we_work/amazon/about_the_amazon/ |

|

| http://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/ |

In the Amazon there is consistently high precipitation, high humidity, and high temperatures. While located in just a single region of the world, the Amazon has an effect on the whole globe. Known as “the lungs of our planet,” the Amazon alone is responsible for producing about 20% of the world’s oxygen; thus, the consequences of any destruction of the Amazon can be felt throughout the entire planet.

Biodiversity

The Amazon Rainforest alone contains ten percent of the known species on Earth with over 40,000 plant species, including 1,000 different species of trees (2,7). One hectare of the rainforest has 600 species of trees.

History

The Amazon rainforest was most likely formed during the Eocene age, appearing when the Atlantic Ocean widened enough to provide a warm, moist climate to the Amazon basin (1). Around 10 million years ago, waters from the west worked through sedimentation to create the Amazon lake. With the formation of the Andes mountains, the waters changed direction to flow eastward. During the Ice Age with water being trapped in ice, sea levels dropped even further, draining the Amazon lake and turning it into a river. Three million years later, ocean levels dropped again, just enough to create a narrow land passage - or isthmus - between Central and South America, allowing mass migration of mammal species to the Amazon Basin. Thus, the biodiverse Amazon rainforest was born (8).

|

| http://www.unique-southamerica-travel-experience.com/amazon-rainforest-climate.html |

Biodiversity

The Amazon Rainforest alone contains ten percent of the known species on Earth with over 40,000 plant species, including 1,000 different species of trees (2,7). One hectare of the rainforest has 600 species of trees.

History

The Amazon rainforest was most likely formed during the Eocene age, appearing when the Atlantic Ocean widened enough to provide a warm, moist climate to the Amazon basin (1). Around 10 million years ago, waters from the west worked through sedimentation to create the Amazon lake. With the formation of the Andes mountains, the waters changed direction to flow eastward. During the Ice Age with water being trapped in ice, sea levels dropped even further, draining the Amazon lake and turning it into a river. Three million years later, ocean levels dropped again, just enough to create a narrow land passage - or isthmus - between Central and South America, allowing mass migration of mammal species to the Amazon Basin. Thus, the biodiverse Amazon rainforest was born (8).

Human Impact

In the past few decades, human settlement and its effects on the Amazon have increased due to an increasing population, the introduction of industrial agriculture, and the Amazon region’s expanding role in the global economy (1). The biggest human impact on the Amazon Rainforest has been deforestation; about 20% of the rainforest has been cut down in the past 40 years, more than all the several hundred years since the beginning of European colonization in the region (3). There are many reasons for this increased human involvement in the region. People see tremendous economic opportunity in the Amazon rainforest for its usefulness in cattle grazing, agriculture, and timber.

Effects

Human involvement in the region has not only directly damaged the rainforest, but it also has left land more vulnerable to future destruction. Logging is the primary cause of forest disturbance; even forests that are selectively harvested are at greater risk of deforestation (1). The most destructive aspect of logging is the building of roads involved; nearly every road in the Amazon is unauthorized, making the forest more accessible and facilitating the illegal logging of mahogany and hardwoods (3).

The Amazon River itself is also affected, as the runoff from the pastures in the region contaminates its waters

Causes of Deforestation

|

| http://www.treehugger.com/culture/adventure-ecology-brings-the-amazon-to-london.html |

Causes of Deforestation

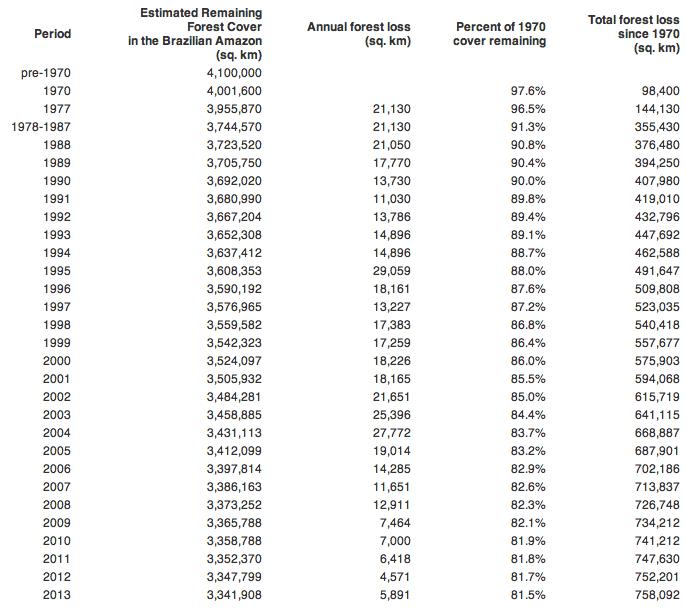

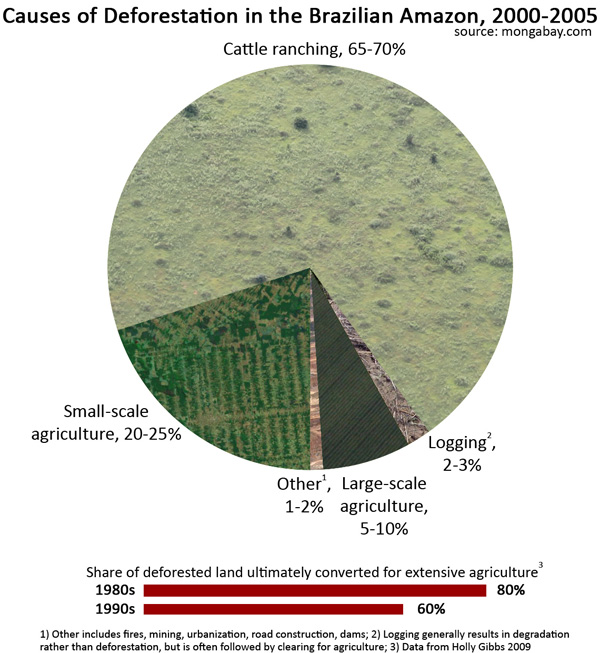

Since the 1970s, more than 1.4 million hectares of forest have been cut (1). By far, thebiggest single direct cause of deforestation is the conversion of land for cattle grazing. Cattle pastures alone make up 80% of the deforested area in the Amazon Rainforest (2). So much land is used for cattle ranching when in return, the pastures have very low productivity and produce only enough to support less than one head per hectare (1). The fire used to manage these fields often spreads into the remaining forests, destroying a forest where fire is not a natural occurrence (2). Another major reason for deforestation in the region is industrial agricultural production, especially for soy farms. The growing industries for cattle and soy are displacing small farmers in the region, forcing them to clear land to sustain themselves—this subsistence form of agriculture is also a leading driver of Amazon deforestation (2). Mining, urban expansion, and timber plantations also join together to contribute to more loss of forest in the Amazon region.

|

| http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/44634000/gif/_44634046_am_hardwood_beef_466.gif |

|

| http://klhaynes247.wordpress.com/research-paper/ |

The Amazon and Climate Change

There is a close relationship between the condition of the Amazon Rainforest and the state of climate change. As one of the world’s largest climate stabilizers, the rainforest acts as a carbon sink and contains 90 to 140 billion metric tons of carbon (2). This means that the destruction of the forests in the region would release significant amounts of carbon dioxide, an earth-warming greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. In the deforestation directly caused by the clearing of land for ranching alone, 340 million tons of carbon are released into the atmosphere every year. Up to 40% of the carbon loss from deforestation in the Amazon (carbon released from the trees when they are cut down) can come from just forest degradation alone, not necessarily full-scale deforestation; therefore in order to be successful in the prevention of carbon loss both forest disturbance and deforestation need to be prevented (9).

Global temperature also has a significant impact on the Amazon.

Increasingly higher temperatures in the tropical Atlantic region leads to reduced rainfall, which can lead to drought (1). The Amazon suffered its worst droughts of the last 100 years in 2005 and 2010 (2). These dry spells make the rainforest more susceptible to fire, and since fire does not naturally occur in a rainforest and the trees are not adapted to such conditions, theses fires are destructive and can add to the already devastating deforestation in the region.

Protected Areas and Future Prospects

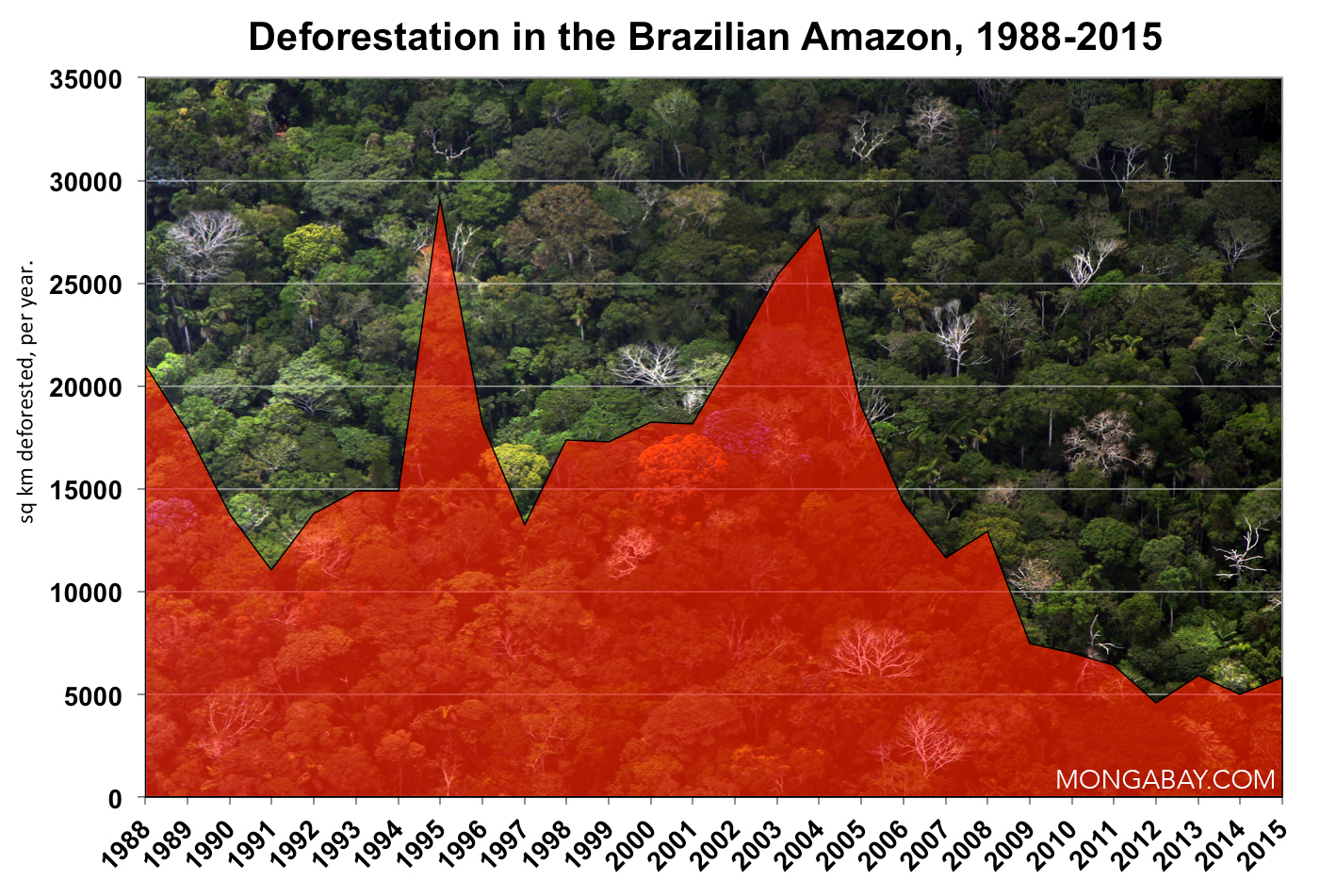

If deforestation—as a result of agriculture, urbanization, and logging—is to continue at its current rate, then the entire Amazon Rainforest could be depleted by the end of the century (5). In response to such a threat, protected areas have begun to be established in an attempt to conserve such a valuable ecosystem. Nearly 44% of the Amazon is now covered by protected areas; in fact, Brazil—which contains most of the rainforest—set aside more land to be protected than any other country in the 2000s (4). Unfortunately, the conditions of such protected areas is very poor. Half of these areas have no approved management plan, staffing is low, and many suffer from encroachment. Illegal mining and logging are the biggest threats to protected areas (4). While the destruction of the Amazon rainforest continues, the overall rate of deforestation is decreasing due to the establishment of such protected areas and has decreased sharply since 2004, when Brazil began its deforestation reduction program (1).

|

| http://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/ |

POSSIBLE IMPROVEMENTS

Many actions can be taken to improve the relationship between the

people and this ecosystem to ensure that we as humans can still benefit

from all the Amazon has to offer while conserving the very natural

resources we benefit from. In response to the land thievery and illegal

logging that takes place, countries—following the example of Brazil—can

use electronic logging certificates to make sure only those certified to

cut down trees in the forest are doing so (3). The management of protected

areas should also be greatly improved. All protected areas should have

a clear management plan and the proper funding to hire enough staff to

carry out any duties required to maintain the land. In addition, more land

should be set aside for protection to ensure the conservation of the

forest, while the rest of the ecosystem can still be available for

sustainable human use. Such improvements are already taking place, with

the Brazilian government and the World Wildlife Fund partnering to create

a fund “to ensure long-term protection of the world’s largest network

of protected areas—150 million acres of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest”

(6). All countries with the rainforest in their borders can utilize

improved law enforcement, satellite monitoring of the region, and

financial incentives for respecting environmental laws.

Works Cited

1. "The Amazon Rainforest." Mongabay.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.

<http://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/>

2. WorldWildlife.org. World Wildlife Fund, n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.

<http://www.worldwildlife.org/places/amazon>

3. "Amazon Rain Forest." Last of the Amazon. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

<http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2007/01/amazon-rain-forest/wallace-text>

4. "Amazon Rainforest News: Protected Areas Cover 44% of the Brazilian

Amazon." Amazon Rainforest News: Protected Areas Cover 44% of the Brazilian

Amazon. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

<http://www.amazonrainforestnews.com/2011/04/protected-areas-cover-44-of-

5. "Rainforests Of Brazil." Rainforests Of Brazil. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

< http://www.brazil.org.za/rainforests-of-brazil.html#.VGMT8fTF9i4>

6. "Amazon Rainforest Gets $215 Million Boost in Protection." Nature World News

RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

< http://www.natureworldnews.com/articles/7300/20140529/amazon-rainforest-gets-

215-million-boost-in-protection.htm>

7. "The Amazon in Graphics." BBC News. BBC, 05 Dec. 2008. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

< http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7360258.stm>

8. "The Amazon Rainforest." The Amazon Rainforest. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2014.

<http://theamazonrainforest.org/>

9. Berenguer, Erika, et al. "A Large-Scale Field Assessment of Carbon Stocks in

Human-Modified Tropical Forests." Global Change Biology 20.12 (2014): 3713-

26. ProQuest. Web. 2 Dec. 2014.